Apart from all of our individual projects, we had another goal: to find a way for all four of us to play together. What kind of piece would work for a combination of violin, piano, electronics, and analogue objects? This question festered in the back of our minds as we researched. We needed something that would have a clear reason for being, something that could sum up our three years together, using either a combination of what we had applied earlier or a new kind of impetus informed by who we were. Something similar had been done 50 years ago: Mauricio Kagel’s piece Ludwig van, which we had studied early on in our project as an early application of new compositional techniques to a historical model. We had studied the score, the film, and an LP recording from 1970 during the first year of our project when the pandemic kept us from meeting and playing together. The piece itself has become iconic, which is likely something other than what Kagel himself would have wanted, the subject of many attempts to recreate the work according to his ”rules,” which are spelled out in the preface to his score. The score itself is comprised of photos of furniture and objects that are papered over by notes written by Beethoven that are used in the film. Kagel’s instructions call for the notes in the score to be used in any order. The notes are taken from chamber music works by Beethoven, but Kagel states that it is also possible to add other notes from other pieces by Beethoven at will. His composition for the LP was based on Beethoven’s own Diabelli Variations, in that Kagel applied his own compositional techniques in a similar manner to the way Beethoven applied his own compositional techniques to a waltz by Diabelli. The instructions are at the same time quite strict and quite open, and it would have been possible for the four of us to perform this piece as a comment on our own work.

We realized however that we were falling into the ”work” trap again, and that it would be much more fitting for our project to shift focus back to the interpreter. So we decided to create a performance that was based on Beethoven but that did not follow the rules of Ludwig van, instead creating our own rules. These were then treated as tasks to be completed, or problems to solve. We decided to call this project ”Van-ish”. In this way we were using our own experience as interpreters to create a performance where we ourselves were the source, although the notes already existed, and the associations and forms inherent to the piece are decontextualized to the point that they are overtaken by the moment.

Our rules were simple: we were allowed to play any notes from Beethoven’s symphonies using any form of tone color, tempo, or volume, but not allowed to change or add any pitches. We were to draw more upon the experiences we ourselves have encountered In our lives working with new music than any experience we had of ”Beethoven” in order to create a performance we could believe in.

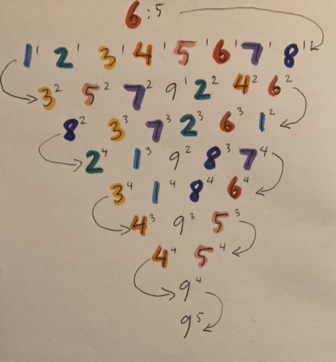

Like all appropriation-based art, the process involved quite a bit of negotiation between the four of us. For example, what parts of what symphonies should we play? Should we play more or less the same sections, more or less together? How should we order the parts of each symphony, and how should we order the overall form of the performance? We decided that all four of us would choose one section from each symphony to work with, and we would then meet and work together.

The first rehearsals were of course horrifying, and we were not especially sanguine about the prospects for performance. But we programmed it anyway at a concert in Kiel, giving ourselves a deadline to figure something out.

After rehearsing, we saw that the choice of notes themselves was less important than the choice of playing styles. So we decided to take parts of each symphony that we individually thought were meaningful, and then force the four of us to fit these together– or not– through assigning them specific kinds of 20th century compositional techniques and playing styles, one to each symphony. In this way, the progression of the concert would depend more upon sound colors, volume and our chamber musical instincts in the moment than on exactly which tones were being played. This allowed us to de- and recontextualize the well-known notes of the symphonies and create different expectations in the audience than those usually associated with ”Beethoven”. We could work together onstage to make sure the pieces fit whether or not there actually was a ”work” to perform. It ended up being a performance where we do what we do as musicians, which is simply to do the best we can in the situation, using what we know.