”… the most fundamental description of what translators do is we write– or perhaps rewrite– in language B a work of literature originally composed in language A, hoping that readers of the second language– I mean, of course, readers of the translation– will perceive the text, emotionally and artistically, in a manner that parallels and corresponds to the esthetic experience of its first readers. ”

Edith Grossman ”Why Translation Matters,” p 7. Yale University Press, 2010.

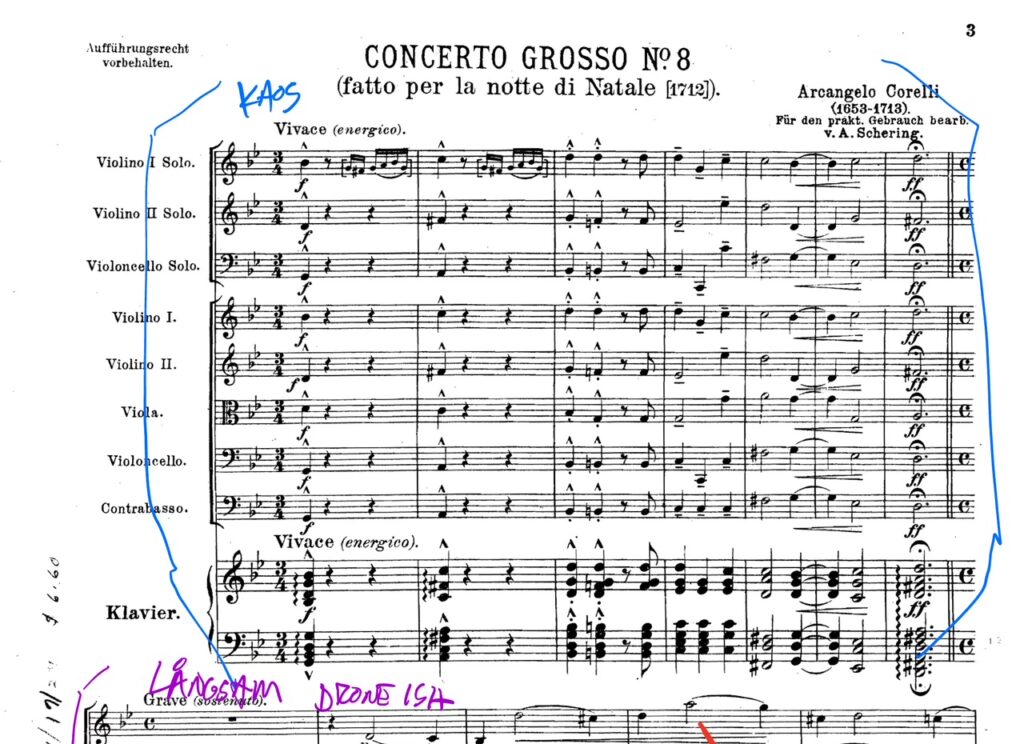

This short answer to the question of what a literary translator does was the starting point for a project initiated by myself and Mattias Petersson. What would happen if we looked at our contemporary musical language in the same way that a translator looked at their target language? If a piece of music was written in the early 1700s such as, say, Corelli’s Concerto Grosso N. 8 from 1712, can we really say that the language used in the composition of that piece is the same as the language we use today when we play music? The way we sound and the societies we live in have changed inexorably over the past 300 years. If the point of a literary translation is the perception of a text ”in a manner that corresponds to the esthetic experience of its first readers”, doesn’t that sound like a worthy goal for an interpreter of a musical work? But to do this in a literary translation is to absolutely not be trying to copy the original.

In ”The Task of the Translator,” Walter Benjamin differentiates between literal translations and those that attempt to find common denominators between the original and the translated version.

”… any translation that intends to perform a transmitting function cannot transmit anything but communication- hence, something inessential. This is the hallmark of bad translations.” (Selected Writings Volume 1, p 253. Belknap Press.) For him, what is important is that which “lies beyond communication” in the original, something that is only possible to translate if the translator is also a ”poet”. Using this to create an analogy, if we interpret a historical work of music by trying to make it sound as if the composer were writing today, in our own current (musical) language, then the interpreters must also be ”poets”, ie, creative musicians, or what are commonly called ”composers”. We may not (should not) be writing the same sorts of notes, in the same ways, but we are using the tools and musical languages available to us to evince a feeling that may or may not mirror the way the original audience felt when listening, but definitely mirrors what we hear when we hear the work.

When we worked on this we looked at the idea of different musical events serving different functions: both obvious ones like fast-slow, loud-soft, asymmetric phrasing etc, but also larger sections of the work and their relationship to the whole. Our ”translation” consists of finding our own personal equivalencies to what we hear when we hear this music and results in a version that we can perform in the contexts in which we make music.

Of course, if we want to speak about musical languages, we see that we are not simply constrained by historical differences if we want to experiment with the idea of translation. In another project, we were also given the opportunity by the composer Leo Correia de Verdier to remake a newly composed piece in any manner we chose, which one could see as a way of translating one specific contemporary language for another. The written piece was a five-minute duo for two violins which we were to perform at a concert together with three other groups of violinists. One duo performed Leo’s piece, one improvised together with electronics, and one duo used a graphic score created by an artist’s rendering of the sounding original. Our project was simply to take these notes and create something in our own language. The fact that this does not happen as often as the translation of older models has more to do with the modern system of copyright than with any technical or artistic difficulties associated with the task.